In the real world, there is no such thing as a zero width wall. Similarly, you can't have a radio transmission with zero bandwidth.

Let's say, hypothetically, that you have a transmitter that is only putting out a sine wave. However, if this is a real (i.e., practical) transmitter, it has instabilities that cause its frequency to wobble a teeny bit, so that "single frequency" actually varies around a center frequency and causes the signal to have a bandwidth.

Now, if you want to also transmit information along with this sine wave, you have to modulate the information into the signal. In order for that signal to contain the information, its bandwidth must increase. A transmission with no bandwidth can't contain any information.

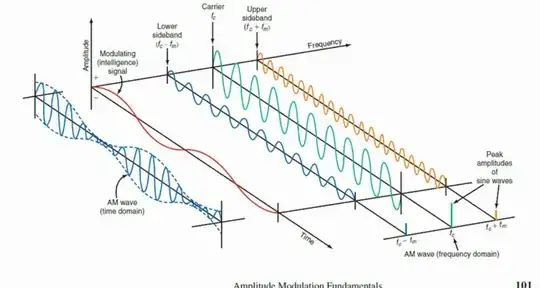

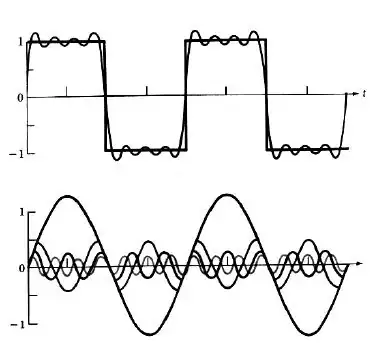

This increased bandwidth results in the signal now covering a range of frequencies. The terms "Amplitude modulation" and "Frequency modulation" might imply that the frequency doesn't change, or the amplitude doesn't change, but that's not how it works. Amplitude modulation works by using the audio amplitude to drive the transmission amplitude -- but the frequency also shifts. Frequency modulation uses the audio amplitude to adjust the frequency offset from a center frequency, but the amplitude also changes.

Consider that a transmitter puts a sine wave on an antenna by introducing a sinusoidal varying voltage. When you change the amplitude, you change that voltage from something different from the original sine wave. When you vary the voltage at some frequency (related to the audio signal), you are adding those new frequencies to the sine wave and giving it more bandwidth -- it is no longer just one sine wave at one frequency.

Amplitude, frequency, and phase are all related; when you modulate a signal, you vary all of them through some mathematical relationship, and exactly what that math is depends on the modulation type.

Along with the varying voltage is a corresponding current which may or may not be in phase. The antenna, like all physical things, has a frequency response. The range of frequencies over which the frequency response of the antenna is favorable to transmission is what we call the "bandwidth" of the antenna. As long as the bandwidth of the antenna is greater than the bandwidth of our signal, the antenna will convert our current and voltage waves into radio waves and they will radiate out of the antenna.

You can think of the antenna like a filament in a light bulb. You put power into it and it radiates. Except that the size of the typical radio antenna is a lot closer to the wavelength of the radio wave it radiates than it is with a light bulb.